Our Story

History

Origins in Struggle

Early view of St. John's College (Fordham University). Our University Church is on the far left in the background, and Cunniffe House on the right.

The origins of Fordham University can be traced to 1839 when John Hughes, the Bishop of New York, bought 100 acres at Rose Hill in the Fordham section of what was then Westchester County for $29,750. However, he said, "I had not, when I purchased the site of this new college...so much as a penny to commence the payment for it." After a nine-month campaign the most money he could raise locally was $10,000, and so he went to Europe on a begging trip to get the funds that he could not raise at home.

The financial difficulties that John Hughes faced in starting St. John's College are indicative of the poverty of the New York Catholic community in 1841. It took a brave man to start a college under such circumstances, but Hughes, an Irish immigrant himself, saw education as the indispensable means for his immigrant flock to break out of the cycle of poverty and better themselves economically and socially in their adopted homeland. "The subject that of all others that he had nearest his heart was education," said John Hassard, an early graduate of St. John's College and Hughes's first biographer.

St. John's College opened its doors in 1841 as a diocesan institution with a grand total of six students. If money was a problem, an even bigger problem was finding capable teachers and administrators among the diocesan clergy. During its first five years as a diocesan institution, Fordham had no fewer than four presidents. Two went on to fame and glory. The first president was John McCloskey, who succeeded Hughes as the second archbishop of New York in 1864 and became the first American cardinal in1875; James Roosevelt Bayley, the last diocesan priest to head the institution, was a convert from a distinguished New York Episcopalian family who became the first bishop of Newark and later the archbishop of Baltimore. However, diocesan clergy of such caliber were the exception rather than the rule in New York.

The Coming of the Jesuits

For both financial and personnel reasons, in 1846 Bishop Hughes was happy to sell St. John's College to a religious order with an international reputation as professional educators. The presence of the Society of Jesus in the United States dates from the establishment of the Maryland colony in 1634. However, the Jesuits who arrived at Rose Hill in 1846 were not Maryland Jesuits, but exiled French Jesuits who were conducting a faltering college in the wilderness of Kentucky. They were delighted to move from frontier America (where it was necessary to place spittoons even in the college chapel) to a site only seven miles from the largest city in the United States, and Hughes was pleased to obtain their services. It seemed to be mutually advantageous for both sides, although there were to be a number of difficult moments for the Jesuits as long as John Hughes was alive.

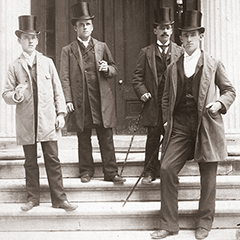

Archbishop Hughes welcomed Jesuits to campus in 1846.

Throughout the later nineteenth century St. John's College remained a small liberal arts college, which was overshadowed by its upstart rival, the Jesuit College of St. Francis Xavier on West 16th Street, which developed into the third largest Jesuit college in the United States and Canada. At St. John’s there was little change in either the size of the enrollment or the curriculum or the daily routine of the students over the course of the first seventy years. As late as 1907 Archbishop John Hughes would have recognized it immediately as the diocesan college that he had founded in 1841. In fact, there was at least one alumnus still alive who had graduated before John Hughes sold the school to the Jesuits in 1846.

In 1907, the year that Francis J. Spellman, the future Cardinal Archbishop of New York, arrived at Rose hill as a first year, St. John's College was still a small school with only 109 students. They were roused from sleep at 6 a.m., attended daily Mass at 7 a.m., were back in their rooms by 7 p.m., and were expected to be in bed by 9 p.m. In Spellman's graduation class of 1911, there were twenty-eight students, equally divided into fourteen boarders and fourteen commuters. The entire teaching staff consisted of twelve Jesuits, ten priests and two scholastics. They had no problem teaching elective courses because they did not offer any elective courses. The standard curriculum was a classical course with heavy emphasis on Latin and Greek leading to an AB degree. The tuition, including room and board, was $200 per semester.

From College to University

In 1904, three years before Spellman’s arrival at Rose Hill, the president, Father John J. Collins, SJ, announced that St. John's College would become a university, but the transition from St. John's College to Fordham University was a gradual process, spread over several decades, with a number of setbacks and false starts. The process began in 1905 with the opening of the first two graduate schools. The first graduate school, the Medical School, lasted only sixteen years and was discontinued in 1921 due largely but not solely to financial reasons. However, the second graduate school, the Law School, flourished from the beginning despite a nomadic existence that necessitated four changes of location in the first ten years.

Seven Blocks of Granite in 1936

In the fifteen years between 1905 and 1920 Fordham gradually assumed the dimensions of a genuine university with the establishment of a College of Pharmacy (which closed in 1971) and at least the foundations of seven graduate schools, not only in medicine and law, but also the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, the School of Social Service, the Graduate School of Education, and the Graduate School of Business Administration (now the Gabelli School of Business). The final component, the Graduate School of Religion and Religious Education, was added in 1975.

However, it was one thing to change the name of St. John's College to that of Fordham University. It was quite another thing to transform a small men's college into a full-fledged university. The process of change was often difficult, hampered by the lack of endowment, the lack of library and laboratory facilities, the lack of a wealthy and generous alumni, and the heavy teaching load of the faculty, which made it difficult for them to engage in the creative scholarship that a modern university demands of its professors.

It is difficult to avoid the impression that Fordham grew too quickly, even recklessly, in its quest to become a university. In the late 1920s Fordham became something of a graduate diploma mill, conferring more master’s and doctoral degrees than any other Catholic university in the country despite the fact that eighty percent of the 600 graduate students were part-time students and the library facilities were scandalously inadequate. In 1935 disaster struck when the Association of American Universities dropped Fordham from its list of approved institutions. "It was," said Father Robert I. Gannon, SJ, "one of the darkest single days” in Fordham's history.

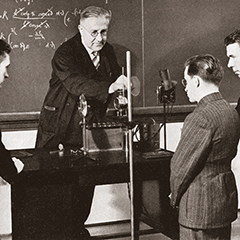

In 1938, Victor Hess, the Nobel Prize in Physics winner for his discovery of cosmic rays, escaped Nazi persecution and found a professional home at Rose Hill.

In 1936 Father Gannon was brought in from St. Peter's College in Jersey City to repair the damage and rebuild Fordham. He has a good claim to be regarded as the first modern president of Fordham University. His twenty-six predecessors had served an average of four years. Gannon remained as president for thirteen years, from 1936 to 1949, guiding the university through the lean years of the Depression and World War II, and overseeing the rapid expansion in the post-war years. He rebuilt the university's shattered academic reputation, curtailed the football program to the delight of some and the outrage of others, and gave Fordham its own radio station. He also separated the office of the rector of the Jesuit community from that of the university president, became an indefatigable fundraiser, and gave Fordham high visibility in New York City through his frequent appearances and speeches at public events. He was the first president of Fordham University to become a well-known figure in New York City.

The Lincoln Center Campus

A major milestone in the development of Fordham University took place with the establishment of the Lincoln Center Campus in the 1960s. Fordham’s new Manhattan campus actually had an inauspicious beginning in December 1954 when Father Laurence J. McGinley, SJ, the President of Fordham, asked Robert Moses, New York City’s master planner and quintessential power broker, if Fordham could rent five floors in the new Coliseum office building to be constructed at Columbus Circle. Moses turned down the request because he explained that the Coliseum was designed for offices, not classrooms However, Moses proposed an alternative solution to Fordham's need for more space. "Why don't you let me bring you in on the urban renewal project a block west of [the Coliseum]" he said to McGinley. The innocent Father McGinley said to Robert Moses, of all people: "What is an urban renewal project?"

Then Robert Moses said to McGinley, "Let's see. How much room would you need? Ten acres?" At that point, Father McGinley admitted, "I almost fell off my chair.... When he mentioned acres, I couldn't believe it. I never heard anyone talk about New York City real estate in terms of acres. I gulped." Robert Moses was not kidding. He whipped out a Manhattan street map and said: "Look, maybe a couple of these blocks; that would be about ten acres or something like that."

This conversation between Robert Moses and Father McGinley, said Father Gannon, "started the most important dream in Fordham's history." When Father McGinley told Cardinal Spellman about his rapidly escalating dream for Lincoln Center, the cardinal replied: "This is the greatest thing that has happened to Fordham since my predecessor Archbishop Hughes built [St. John's College] up at Rose Hill. The Lincoln Center campus of Fordham University gradually took shape between 1961, when the new Law School building was dedicated, and 1969, when the Lowenstein Building became the home of a new liberal-arts college and the graduate schools of Education, Social Service and Business Administration (now the Gabelli School of Business).

Fordham made major strides in achieving its goal of becoming a national rather than a local or regional institution during the nineteen-year presidency of Father Joseph O’Hare, SJ In 1972, 72 percent of Fordham undergraduates were commuters; twenty years later, 70 percent of Fordham undergraduates lived on campus. The transition was made possible by the construction of over 3,500 new student residential units. The opening of the Walsh Family Library in 1997 was an essential ingredient in Fordham’s bid to become a serious research institution. In 1997 U.S. News and World Report ranked Fordham Law School 28th out of 179 law schools nationwide, and it ranked the Graduate School of Social Service 11th out of 127 such programs across the country.

While Fordham made a determined bid for national recognition, it did not neglect its ties to the local community. An extensive and successful Higher Educational Opportunity Program (HEOP) enabled many minority students to complete college. Fordham also gave a tuition rebate of $4,000 to Bronx students who lived at home. The Graduate School of Education cooperated closely with the New York City public schools, and the first African American and the first Hispanic public school principals in the New York City were educated at Fordham. In the early 1980s the Graduate School of Social Service had a higher number of Hispanic students than any other American university except the University of Puerto Rico. Under Dean John Feerick, a native of the South Bronx, Fordham Law School sponsored a number of initiatives and research centers to benefit the local community.

The Fordham Law School building and McKeon Hall opened on the Lincoln Center campus in 2014.

Excelsior

In 1841 Bishop Hughes was able to raise locally only one-third of the $30,000 that he needed to pay for the acquisition of the property at Rose Hill. A century later Father Gannon was only able to raise little more than half of the one million dollars that he set as the goal of Fordham’s centennial fund-raising drive. By contrast, when Father Joseph M. McShane launched the Excelsior | Ever Upward | Campaign for Fordham in 2009, he boldly set a goal of a half-billion dollars. It was a huge success and raised $540,000,000 from 60,000 contributors.

The single largest contribution (and the largest contribution in Fordham’s history) came from Mario J. Gabelli, CBA ’65, whose generous donation of $25 million made possible the establishment of the Gabelli School of Business in the completely renovated Hughes Hall at Rose Hill. The success of Excelsior also helped to defray the expense of the new law school building and additional residential housing at both Lincoln Center and Rose Hill.

Today, John Hughes’s original investment of $30,000 continues to pay handsome dividends not only for the Catholics of New York, but also for the much larger community that Fordham continues to serve.

Msgr. Thomas J. Shelley

Professor Emeritus, Theology, Fordham University

Author, Fordham, A History of the Jesuit University of New York: 1841-2003